“Within Lincoln Park’s lawns, sculptures, and tree-lined allée live stories of Native American presence, Civil War remembrance, public health reform, immigration, and the city’s recovery after the Great Chicago Fire.”

—Kristin N. Smith, producer of Forged in History: Lincoln Park, Shaping Chicago.

Second only to New York’s Central Park as the most visited urban park in the United States, Lincoln Park today spans more than 1,200 acres. What began as a 19th-century public cemetery has evolved into a living archive of Chicago’s civic past. Zoogoers, joggers, picnickers, and international visitors pass statues of long-departed figures with only a glance, but filmmaker Kristin N. Smith wants to change that.

Phase One included fall filming, with professional cinematographers capturing visuals of Lincoln Park that reveal both its history and artistic design. The documentary will explore overlooked narratives embedded in the park’s landscape and monuments, histories that quietly trace Chicago’s formative chapters.

Smith previously produced David Adler: Great House Architect, which aired nationally on PBS for three years. She is donating her time and expertise to this project as part of her broader work preserving and interpreting historic and cultural heritage.

“When the meaning of a place is understood, it’s more likely to be protected,” Smith said. “This film aims to reconnect people with the stories that give Lincoln Park its enduring civic value.”

For Smith, documenting Lincoln Park now feels particularly urgent. “At a time when urban development increasingly produces interchangeable glass-and-steel skylines, and when local history is fading from classrooms and public awareness, this documentary will explore how civic landscapes help preserve the character that sets cities apart,” she said. “Lincoln Park is more than recreation. It reflects loss, ambition, reform, and our nation’s highest level of artistic vision.”

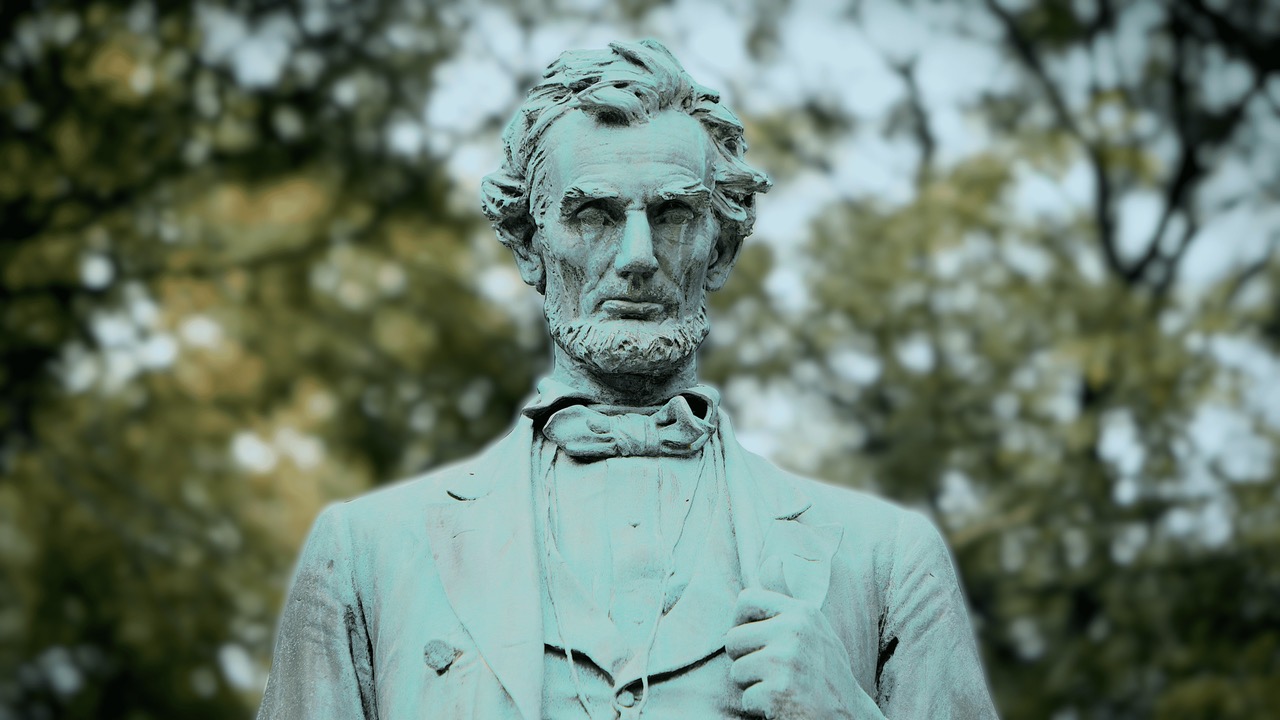

“The bronzes in Lincoln Park weren’t created simply as decoration,” Smith explained. “They show how earlier generations chose to remember leadership, war, loss, and civic ideals.”

Phase Two will soon focus on interviews with leading historians and conservation specialists. A preview clip on YouTube offers an early look at some of the film’s visuals and historical themes.

Smith told us more about what she has discovered about Lincoln Park.

“Originally established as a public cemetery, the land was renamed during the city’s collective mourning following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln in 1865. From that beginning, the park evolved into a national model of civic beauty and public access to green space as Chicago confronted disease, rapid population growth, and sweeping social change.”

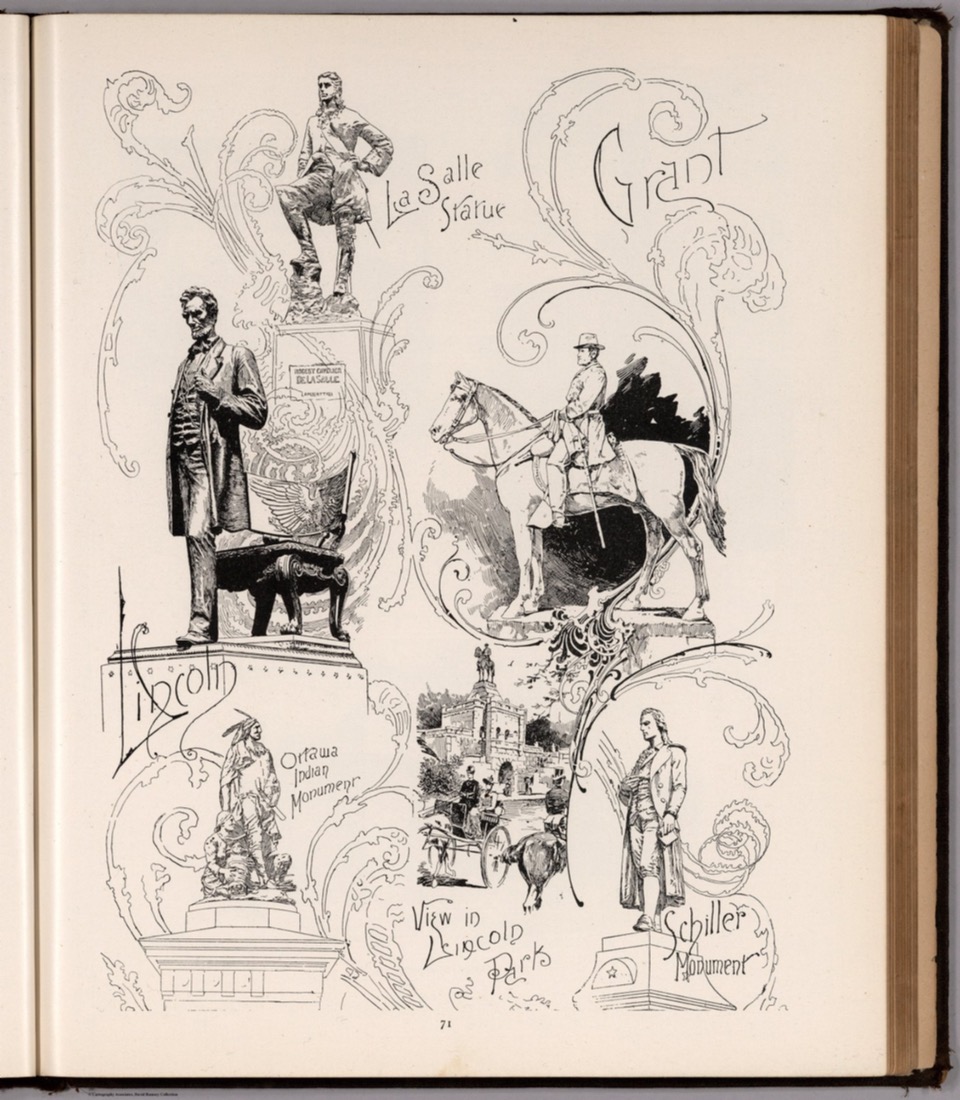

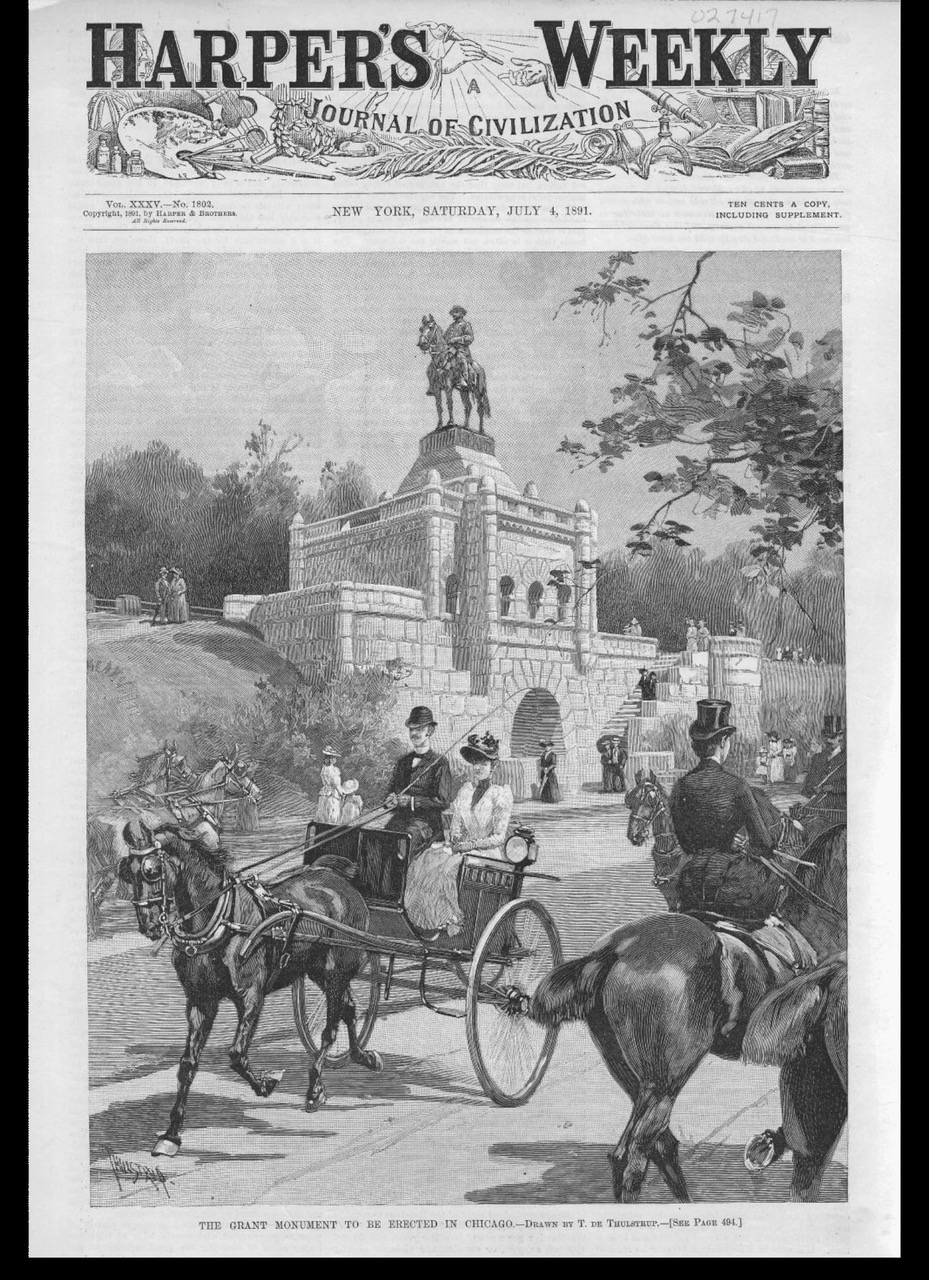

She noted the park’s artistic legacy is equally notable. The oldest statue honors Native Americans, while sculptor Gutzon Borglum, later famed for Mount Rushmore, created both the Governor John Peter Altgeld Monument in 1915 and the General Philip Henry Sheridan Monument in 1923. “Public monument unveilings once drew extraordinary crowds. It’s estimated 200,000 people attended the dedication of the Ulysses S. Grant equestrian statue, roughly one in five Chicagoans at the time, and Abraham Lincoln’s son Robert, along with his namesake grandson, attended the unveiling of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Standing Lincoln,” Smith said.

Yet beneath the lawns and pathways lies a sobering reality: not all of the cemetery’s original burials were relocated.

“Other chapters unfold just as quietly, including the Civil War, the Fresh Air Sanitarium, Temperance, connections to the Haymarket Riot, landfill expansion that created Lake Shore Drive, and more. Together, they reveal Lincoln Park as a historical record hiding in plain sight beneath one of Chicago’s most beloved public spaces.”

Smith said she visited Lincoln Park in a stroller soon after she was born and then biked through it with her brother as a child. As an adult, she crossed the park while commuting nearby and returned on weekends for long walks with her dogs.

“A friend created a series of watercolors of the park’s monuments, later published in her award-winning book, Giants in the Park,” she said. “Her work made me slow down and notice the details around me. While there are many books and blogs about Lincoln Park, film allows audiences to experience these stories visually and emotionally. That’s when I realized I wanted to film the park thoughtfully, to put a camera on the experts and share the stories behind what people see every day.”

One of her favorite places to pause is on a bench at the Little Cold Water Girl/Frances Willard statue close to the LaSalle underpass. It first appeared at the World’s Fair of 1893, erected by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union to urge people to drink water, with cups attached for people and a trough for horses, dogs and birds. After the fair, it was moved to the Woman’s Temple in the Loop and, when that was to be demolished, to Lincoln Park in 1940. Although the statue was stolen, it was re-cast from the original mold. Smith is in discussions to interview the artist responsible for its recreation, who preserves bronze monuments across the city and nationwide.

She also delights in the park’s equestrian sculptures. “I love the horses in the park, President Grant’s war horse Cincinnati and General Sheridan’s Winchester, renamed after one of his Civil War victories,” Smith said. “And it’s wonderful to see children climbing into the lap of an author’s statue in the English gardens. I also like to pause at the Altgeld monument, which feels almost hidden among the trees.”

“Located on the northwest corner of Lincoln Park, the National Elks Memorial, which is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year, has kindly agreed to serve as an in-kind sponsor by hosting the interviews in one of Chicago’s most architecturally significant buildings. The Memorial offers a fitting setting for conversations about civic memory,” Smith said.

The production is proceeding with permission from the Chicago Park District, which is not a sponsor or producing partner of the film. Upon completion, the documentary will first be submitted to PBS for consideration and then made freely available online to residents, visitors, educators, and students.

When asked how visitors should best experience Lincoln Park, Smith recommends taking time to explore it gradually. “There isn’t one perfect path,” she said. “If someone wants the full experience, I suggest a kind of grand tour, which can be followed with a guidebook or at your own pace: a loop that takes you past the park’s monuments, gardens, zoo, lagoons, and lakeshore.”